Sergeant Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (1967)

1.Sergeant Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

2.With A Little Help From My Friends

3.Lucy In The Sky With Diamonds

4.Getting Better

5.Fixing A Hole

6.She's Leaving Home

7.Being For The Benefit Of Mr. Kite

8.Within You, Without You

9.When I'm Sixty-Four

10.Lovely Rita

11.Good Morning, Good Morning

12.Sergeant Pepper Reprise

13.A Day In The Life

If Revolver was the Beatles’ most complete album in terms of musical invention and structural unity, then Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was their boldest statement of cultural intent. Released in 1967, after more than six months and 700 hours of recording time, it was a far cry from their 1963 debut—which had been completed in a single day. This album was not merely a collection of songs; it was a deliberate reinvention, a pastiche of character, costume, and sonic artifice wrapped in a carnival of sound.

The conceit—a fictional Edwardian-era band presenting a performance—is largely thematic rather than narrative. Yet it provides just enough of a framing device to link disparate tracks into something approaching a concept album. From the first bars of the title track, complete with orchestral tuning and audience murmur, we are invited into a parallel world. This is performance not only as music but as mythmaking.

With a Little Help from My Friends, sung by Ringo Starr in the role of “Billy Shears,” stands among the finest of the band’s collaborative compositions. Its emotional core and communal tone make it far more than a novelty track. It also dovetails perfectly with its lively prelude, reinforcing the illusion of a concert in progress.

What follows is a kaleidoscope of styles and techniques: Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds, often wrongly assumed to be a thinly veiled ode to LSD, is more accurately a dreamlike waltz through Lewis Carroll’s subconscious, bolstered by Lennon’s vivid wordplay and a warbling Lowrey organ. Getting Better and Fixing a Hole are McCartney at his most tuneful, quirky, and precise—songs that balance optimism with undercurrents of uncertainty. She’s Leaving Home, bolstered by Mike Leander’s string arrangement, is a rare example of a Beatles song produced without George Martin’s orchestration, yet its narrative pathos is undeniable.

George Harrison’s Within You Without You, a full-scale Indian raga complete with tabla and dilruba, pushes the Eastern influence introduced on Revolver to its most expansive and serious expression. For many, it is a contemplative centerpiece; for others, an alienating diversion. Regardless, its ambition is undeniable.

If McCartney’s flair for nostalgic pastiche peaked with When I’m Sixty-Four—a music hall number as affectionate as it is arch—his contribution to the album’s finale is something else entirely. A Day in the Life, co-written with Lennon, is not only the most ambitious piece the band had yet attempted, but arguably the most accomplished. Its seamless fusion of two unfinished songs, one ethereal and haunting, the other mundane yet surreal, culminates in a thunderous orchestral crescendo and the most famous final chord in pop history. It is the sound of the 1960s simultaneously ending and beginning again.

Technically, the album is a triumph. George Martin’s production techniques—varispeed tape, automatic double tracking, reverse recording—were not only pioneering but essential to the record’s distinctive atmosphere. Instruments were manipulated like characters; the studio became the fifth Beatle in earnest.

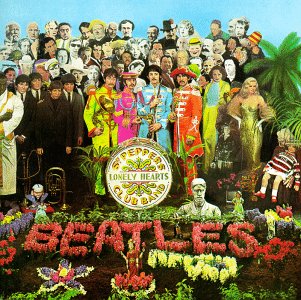

The visual presentation cannot be overlooked. The cover, a pop-art tableau of cultural icons surrounding the Beatles in psychedelic military garb, is as iconic as the music itself. It elevated the LP sleeve to an art form, prompting listeners to engage with albums not merely as music but as multi-sensory experiences.

In the final accounting, Sgt. Pepper may not be the Beatles’ most consistent or cohesive album, but it is certainly their most influential. It codified the idea of the studio album as art object. It shaped the course of popular music, not only in sound but in ambition. That its songs have been dissected, mythologized, parodied, and occasionally misunderstood only reinforces its stature.

As a cultural document, it is peerless. As a musical achievement, it is daring, uneven, and often breathtaking. It remains one of the few albums whose reputation as a watershed moment in popular music is not hyperbole but plain fact.