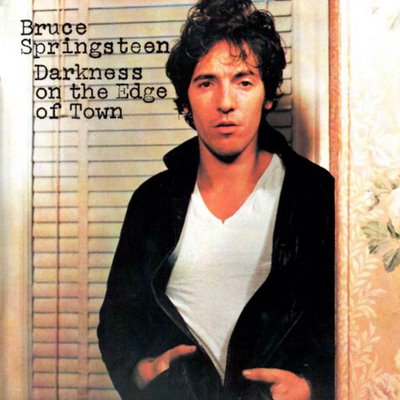

Darkness on the Edge of Town (1978)

1. Badlands

2. Adam Raised a Cain

3. Something in the Night

4. Candy's Room

5. Racing in the Street

6. The Promised Land

7. Factory

8. Streets of Fire

9. Prove it all Night

10.Darkness on the Edge of Town

Following the explosive success of Born to Run, Bruce Springsteen found himself not on tour, but in court. A protracted legal dispute with former manager Mike Appel prevented the release of any new material for three years—an eternity in the mid-1970s, when audiences and record labels alike expected annual output. The delay might have derailed a lesser artist. Instead, Springsteen used the enforced hiatus as a crucible, honing his craft and stockpiling songs that would form the basis of both this album and a still-legendary archive of unreleased material.

When Darkness on the Edge of Town finally arrived in 1978, it met—and in many ways surpassed—those long-nursed expectations. It was not Born to Run II, nor was it meant to be. Where that earlier record exploded with youthful urgency and romantic escape, Darkness channeled something colder, harder, and more grounded. The dreams were still present, but they had grown bruised. The small-town streets were no longer springboards to glory, but battlefields for dignity.

Musically, the album is leaner, more focused. The E Street Band, now operating as a taut, well-oiled unit, delivers a muscular backdrop to Springsteen’s increasingly stark narratives. The addition of Max Weinberg and Roy Bittan had already enhanced the band’s sonic depth; here, their contributions—particularly Bittan’s piano and Weinberg’s unflinching rhythms—are central to the album’s emotional terrain.

Lyrically, Springsteen pares back the florid imagery of earlier records in favor of grit and directness. Badlands, The Promised Land, and the title track offer no easy redemption—only endurance, and the faint hope that perseverance might, someday, pay off. These are not anthems of escape, but of survival. Even when couched in the trappings of rock and roll, the content is often bleak: characters who fight, falter, and, most crucially, keep going.

Critics at the time noted a sense of thematic redundancy creeping into Springsteen’s work—too many songs set in the “night,” on the “street,” and powered by some kind of existential “fire.” There is some truth in this. His palette remained narrow, but it was also increasingly refined. If the stories echo one another, it is because they form part of a collective narrative—of lost chances, stubborn hope, and the struggle to define one’s life in defiance of circumstance.

Darkness may not have charted new musical terrain in the way Born to Run did, but it marks a profound step forward in artistic maturity. Gone is the theatrical flourish; in its place, a raw emotional realism. It is the sound of Springsteen narrowing his focus and digging deeper.

For some, this remains the pinnacle of his recorded work—a record that captures the essential Springsteen dialectic: dream versus duty, promise versus limitation. Whether or not it stands as his greatest album is a matter of taste, but there is little doubt that Darkness on the Edge of Town represents a cornerstone in one of the most consequential careers in American rock music. It is as uncompromising as it is essential.

Go back to the main page

Go To Next Review