Fleetwood Mac (1968)

1. My Heart Beat Like a Hammer

2. Merry-Go-Round

3. Long Grey Mare

4. Hellhound on My Trail

5. Shake Your Moneymaker

6. Looking for Somebody

7. No Place to Go

8. My Babys Good to Me

9. I Loved Another Woman

10.Cold Black Night

11.The World Keep on Turning

12.Got to Move

Fleetwood Mac. Say the name and for most it conjures images of sun-drenched California harmonies, intra-band romantic dramas, and the sweet sorcery of Rumours. Yet to reduce the band to that mid-'70s incarnation is to ignore an earlier, rawer genesis—one that belongs to a wholly different musical universe. Long before Buckingham's precision or Stevie Nicks’ velvet mystique, Fleetwood Mac were a blues band. A proper, hard-line, British blues band.

Only two names connect those two worlds: drummer Mick Fleetwood and bassist John McVie—hence the band’s moniker, and arguably their only enduring throughline. Neither sang. Neither wrote. But together they formed the granite foundation upon which a kaleidoscope of identities would later be built. In the late 1960s, that identity was almost singlehandedly shaped by guitarist and vocalist Peter Green, with slide man Jeremy Spencer rounding out the frontline.

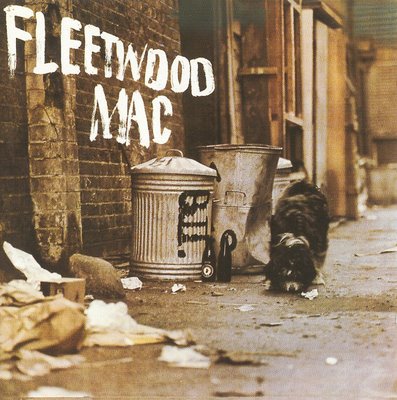

This eponymous debut album, released in 1968, is not to be confused with the similarly titled 1975 effort that launched the band into superstardom. Fans of the earlier era know to call this Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac or The Dog and Dustbin—the cover art helpfully pointing the way. And what a debut it is. While steeped firmly in blues tradition, the album radiates a freshness and a commitment that elevated it above the glut of British blues imitators cluttering the clubs at the time.

From the opening bars of My Heart Beat Like a Hammer, it’s clear this is no half-hearted homage. Jeremy Spencer channels Elmore James with uncanny accuracy, while the rhythm section moves with unflappable restraint. But it is Green—blessed with a tone so fluid, so mournful—that sets the album apart. His work on I Loved Another Woman is revelatory. Here is blues filtered through a late-sixties haze, full of soul and soul-searching, yet never pastiche. The song may follow the expected 12-bar form, but Green’s phrasing elevates it into something haunted, almost cinematic.

There’s range, too. Shake Your Moneymaker tears through the speakers like a bar brawl at last call, all energy and swagger. No Place to Go borrows its groove from Booker T. and Steve Cropper’s Green Onions, but adds a rougher, more volatile edge—equal parts homage and reinvention. Even The World Keep on Turning, a stripped-down acoustic number with Green alone at the mic, suggests depths that far outpace the band’s young years. It’s less a song than a confession, full of space and sorrow.

Spencer deserves his due. While Green provided the emotional anchor, Spencer’s commitment to blues orthodoxy gave the album a thrilling duality. His vocal stylings and slide work are so steeped in tradition they border on ventriloquism, yet somehow never descend into parody. Together, they formed an unlikely, but thrilling, balance—Green the innovator, Spencer the preservationist.

And here lies the album’s most astonishing quality: its ability to sound both reverent and entirely contemporary. Where many of their contemporaries floundered in mimickry, Fleetwood Mac brought new textures to an old form. They didn’t so much modernize the blues as reframe it, giving it a distinctly British, subtly psychedelic edge—one that would echo for decades.

It’s a bittersweet listen now. Personnel changes—frequent and often calamitous—would become a defining feature of the band’s DNA. Green, the heart and soul of this iteration, would soon depart under tragic circumstances, taking with him the ethereal magic that powered these early records. The band would go on to greater commercial success, but they would never again sound quite like this.

Fleetwood Mac’s debut is more than just a promising first step. It is a fully realized blues statement that deserves to stand with the best of its kind. Gritty, impassioned, and often sublime, it captures a moment when the blues, so often worn like borrowed clothes, was felt deeply—and played as if it belonged to them.

Go back to the main page

Go To Next Review