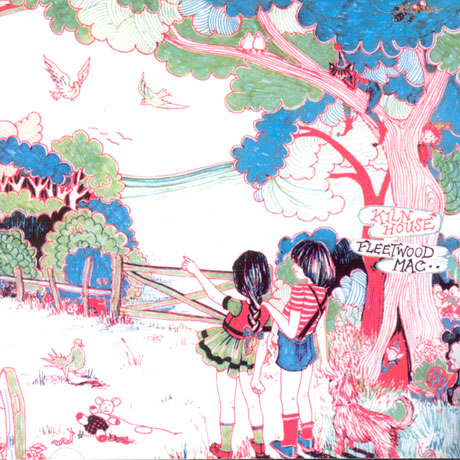

Kiln House (1970)

1. This is the Rock

2. Station Man

3. Blood on the Floor

4. Hi Ho Silver

5. Jewel Eyed Judy

6. Buddy's Song

7. Early Gray

8. One Together

9. Tell Me All the Things You Do

10.Mission Bell

It’s a truth universally acknowledged—though often politely avoided—that Fleetwood Mac has weathered more internal chaos than most soap operas. And if the 1969 masterstroke Then Play On marked the peak of their early ambition, then Kiln House, released just a year later in 1970, represents the inevitable crash back to earth.

The cause? The departure—sudden, surreal, and shrouded in psychedelic haze—of Peter Green, the group’s musical cornerstone. The reasons for his breakdown remain speculative (too much LSD? A spiritual crisis? A sudden aversion to success?), but the result was unambiguous: the band's visionary was gone, and the center, predictably, could not hold.

What emerged in Kiln House is less a follow-up than a full-scale musical identity crisis. Without Green’s steadying hand and cerebral touch, the band scrambled not only for direction but, seemingly, for purpose. The album is many things—but cohesive is not one of them.

For better or worse (mostly worse), the dominant personality here is Jeremy Spencer. Previously confined to the occasional blues pastiche, Spencer now takes center stage—and uses the opportunity to indulge a fetish for ‘50s rock and roll forgetfulness that borders on parody. Tracks like Mission Bell, Blood on the Floor, and One Together aim for Buddy Holly but land closer to novelty act. Buddy’s Song—a literal homage featuring lines lifted from the Buddy Holly catalogue—is not only peculiar but practically dares the listener to take it seriously.

Even worse, a cover of Honey Hush is mistitled as Hi Ho Silver, and performed with all the listless energy of a rehearsal room run-through. Whether this is a charmingly shambolic nod to early rock or simply a misfire depends entirely on your patience for nostalgia dressed in yesterday’s leather jacket.

Danny Kirwan, by contrast, offers glimmers of what could have been. Jewel Eyed Judy is a wistful, melodic piece that hints at the soft rock tapestry Fleetwood Mac would later weave with such finesse. Earl Gray, an instrumental, leans back toward the dreamy textures Kirwan had explored on Then Play On, though here the mood feels slightly detached, as though reaching for something that never quite materializes.

Adding to the album’s strange halfway-house quality is the ghostly presence of Christine McVie (née Perfect), who contributes keyboards and vocals to Tell Me All the Things You Do. It’s a pleasant enough track, though hardly revelatory. At this stage she remained more an adjunct than a full-fledged member, a role she would solidify (and elevate) in the very near future.

What Kiln House ultimately offers is not a vision, but a holding pattern. One suspects that even the band wasn’t entirely convinced by the direction, such as it was. The record is caught between past and future, haunted by the absence of Green, and unsure whether to grieve or simply turn up the jukebox and try to dance away the disorientation.

In fairness, some listeners do harbor fondness for Kiln House—perhaps drawn to its rawness, its oddball charm, or simply its place in the Mac’s bewildering evolution. But taken on its own merits, it remains an awkward, transitional artefact: not quite blues, not quite rock, and certainly not the Fleetwood Mac of legend.

It would take further shakeups and at least one more guitarist’s nervous collapse before the group would settle into its next great phase. Until then, Kiln House stands as a curious sidestep—a detour through retro Americana by a band that, for the moment, had lost the map.

Go back to the main page

Go To Next Review