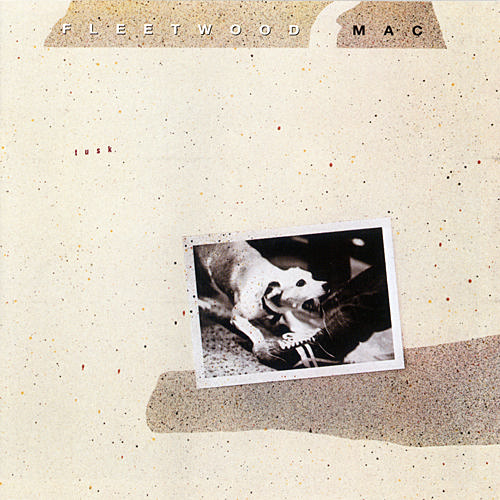

Tusk (1979)

1. Over and Over

2. The Ledge

3. Think About Me

4. Save Me a Place

5. Sara

6. What Makes You Think You're the One

7. Storms

8. That's All For Everyone

9. Not That Funny

10.Sisters of the Moon

11.Angel

12.That's Enough For Me

13.Brown Eyes

14.Never Make MeCry

15.I Know I'm Not Wrong

16.Honey Hi

17.Beautiful Child

18.Walk a Thin Line

19.Tusk

20.Never Forget

How, exactly, does one follow Rumours—an album that sold over 25 million copies, redefined the band’s identity, and embedded itself into the cultural DNA of the late 1970s? The conventional answer, of course, is that you don’t. And to their considerable credit, Fleetwood Mac didn’t try. Tusk, released in 1979, is less a sequel than a purposeful act of self-sabotage, a sprawling, idiosyncratic double album that seemingly dares the listener to stop comparing it to its predecessor. In the process, the band created something baffling, occasionally brilliant, and, in retrospect, oddly essential.

Lindsey Buckingham, increasingly the creative fulcrum of the group, effectively seized the reins on this project. If Rumours was a collaborative exercise in polished pop-rock craftsmanship, Tusk is Buckingham’s art-school tantrum. Gone are the smooth harmonies and FM-friendly contours. In their place: jagged rhythms, barked vocals, tape loops, distorted acoustics, and—yes—a full college marching band. Half of the album is his, and most of those tracks sound like someone trying to exorcise their demons through a four-track machine.

To be fair, there is method in the madness. Songs like Not That Funny, What Makes You Think You’re the One, and That’s Enough for Me flirt with chaos but never quite collapse into it. They’re abrasive, impatient, and often exhilarating—just not particularly tuneful. That Tusk the song—equal parts tribal stomp and studio prank—became the lead single is testament either to Buckingham’s genius or Warner Bros.’ total surrender. And yet, bizarre though it is, Tusk (the track) remains utterly compelling, its hypnotic groove and peculiar sonic textures refusing to be dismissed.

If Buckingham was intent on deconstructing Fleetwood Mac, Christine McVie was there to quietly hold it together. As ever, she plays the role of ballast—unshakable, unshowy, and unfailingly melodic. Her Think About Me offers the closest thing to a traditional single, a crisp, infectious number that briefly recalls the glory days of Rumours. But it’s her deeper cuts—Never Make Me Cry and Never Forget—that truly shine. Understated and emotionally direct, they remind us just how essential her presence is, even when her profile within the band was often overshadowed.

Then there is Stevie Nicks, who arrives here in full command of her mystique. This is arguably her most consistent set of songs on any Fleetwood Mac album. Sara, long regarded as one of her masterworks, is ethereal and elusive, a six-minute dreamscape that shimmers with melancholy and quiet grandeur. Sisters of the Moon channels the darker energies of Rhiannon, its ominous textures and spectral vocals hinting at forces beyond the terrestrial. Even her less-heralded contributions—Storms, Angel, Beautiful Child—glow with introspection and quiet force. If Buckingham was tearing the band apart sonically, Nicks was weaving it together thematically.

And that, ultimately, is the curious triumph of Tusk. On paper, it should fall apart. Three principal songwriters pulling in entirely different directions, a recording process bloated with excess and experimentation, and a deliberate rejection of the formula that had made them global icons. Yet somehow, it works. Not seamlessly, not always beautifully—but with a strange and persistent cohesion that suggests the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

Commercially, it was seen at the time as a relative disappointment—how could it not be, following Rumours? But critically, its stock has only risen. When an indie outfit like Camper Van Beethoven chose to cover the entire album in 2002, it was less a gimmick than a tribute to the strange genius of the original. Tusk was never meant to be an encore. It was a statement. A challenge. A risk.

And like all great risks, it didn’t please everyone. But it ensured that Fleetwood Mac were not just survivors of the 1970s—but active participants in pushing its boundaries. They may have had to lose a bit of polish to get there—but they gained something far more enduring: a very big slice of artistic credibility.

Go back to the main page

Go To Next Review