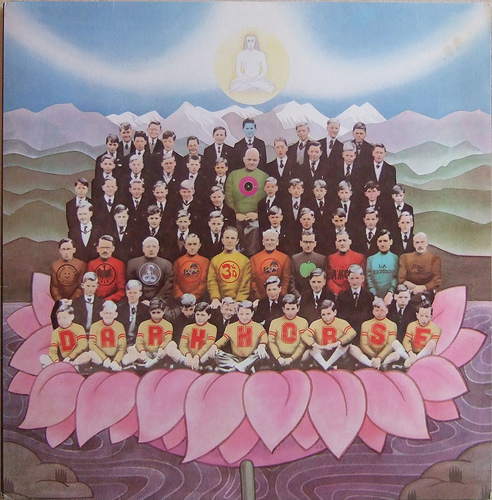

Dark Horse (1974)

1. Hari's on Tour (Express)

2. Simply Shady

3. So Sad

4. Bye Bye Love

5. Maya Love

6. Ding Dong, Ding Dong

7. Dark Horse

8. Far East Man

9. It is "He" (Jai Sri Krishna)

There is little pleasure in saying so, but Dark Horse may well represent the lowest ebb of any solo Beatle’s recorded output. And the most striking aspect of this downturn is the apparent indifference with which it was delivered. Rarely has an album sounded so resigned to its own inadequacy.

To understand it in context, one must remember that albums in the mid-1970s were not always conceived as lasting monuments. Many were expedient, rushed affairs—soundtracks to tours, filler between contracts. Dark Horse seems to fall into precisely that category. It plays like a loose rehearsal, hastily captured and prematurely released. The songs are underwritten, the performances underwhelming, and Harrison himself, audibly ailing, sings much of it as though in the throes of a seasonal flu.

The irony, of course, is that George had already demonstrated he could be a master of the studio. All Things Must Pass proved that. But here, self-producing and seemingly self-isolating, he offers little in the way of polish or persuasion. From the very first track, Hari’s on Tour (Express), it’s clear something is amiss. A limp instrumental, it meanders in search of a vocal line that evidently never arrived. It sounds suspiciously like a backing track left unfinished—a fate that might have been kinder had it remained unreleased. Troublingly, it is also the most coherent piece on the record.

What follows is a murky mix of spiritual musings, personal grievances, and off-key attempts at levity, all marred by strained vocals and slapdash production. The title track limps along with hoarse abandon, while Simply Shady lives up to its name—an introspective confessional clouded by incoherent metaphors and an almost confrontational lack of melody.

The nadir, however, arrives with Bye Bye Love—a deeply awkward unimpressive cover of the Everly Brothers’ classic, repurposed here as a bitter postscript to George’s personal life. It features backing vocals from both his ex-wife Pattie Boyd and Eric Clapton—the man she left him for. The recording’s existence is baffling enough; its inclusion on a commercial album borders on the surreal. Whatever grace might have emerged from such tangled emotional terrain is lost in a haze of bad judgment and worse harmonies.

The absence of a seasoned producer such as Phil Spector is keenly felt. Harrison, for all his artistry, benefited from strong sonic stewardship. Left to his own devices, Dark Horse becomes a case study in unchecked artistic drift. One hesitates to imagine what the album might have sounded like had he been in better voice, with stronger material and a firm hand on the faders. As it stands, those variables are left entirely hypothetical.

Dark Horse exposes the cost of spiritual conviction when not anchored by craft, and the hazards of recording through illness, ego, or both. That Harrison would rebound from this is a testament to his resilience. But here, in this oddly hollow set of songs, the quiet Beatle sounds lost in his own echo.

Go back to the main page

Go To Next Review