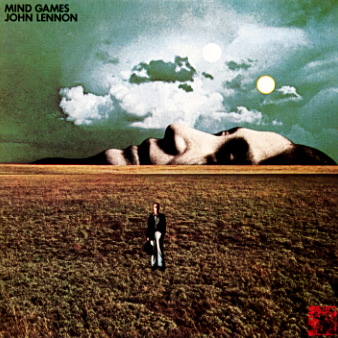

Mind Games (1973)

1. Mind Games

2. Tight AS

3. Aisumasen (I'm Sorry)

4. One Day (At a Time)

5. Bring on the Luci (Freda Peeple)

6. Nutopian International Anthem

(three seconds of silence)

7. Intuition

8. Out the Blue

9. Only People

10. I Know (I Know)

11.You Are Here

12.Meat City

After the confrontational misstep of Some Time in New York City, Mind Games finds John Lennon retreating—if not entirely inward, then at least back to safer ground. Released in 1973, it is arguably Lennon’s most conventional album, and by that same token, his most subdued. Gone are the explicit political manifestos, the guerrilla street chants, and the heavy-handed didacticism. In their place: melody, sentiment, and a reassertion of Lennon as songwriter first, activist second.

The title track opens the album on a high note—a shimmering piece of mid-tempo pop, ethereal in production and wistful in tone. It is, in many ways, a summation of what follows: a gentle blend of introspection and optimism wrapped in sonically lush arrangements. Though Phil Spector is absent this time around, his influence lingers. The production, handled by Lennon himself, carries the ghost of the Wall of Sound—layered vocals, echoing percussion, and a general haze of sonic density that sometimes enhances and sometimes obscures.

There is more musical variety than one might initially suspect. Meat City and Tight A$ inject a dose of rock ’n’ roll swagger, albeit with Lennon’s tongue firmly in cheek. The former in particular feels like a holdover from the Imagine sessions—playful, irreverent, and designed more to amuse than to endure. Bring on the Lucie (Freeda People) nods gently in the direction of political messaging but does so with a warmth and tunefulness that Some Time in New York City sorely lacked. Here, Lennon sounds engaged rather than enraged.

One welcome development is the comparative absence of Yoko Ono’s direct involvement. Her presence is felt—as it always was—but not heard. No vocals, no co-credits, and no overt dedications. The result is a collection of songs that feel more open, more universally accessible. Out the Blue, one of the album’s finest moments, is a tender love song, its lyrics heartfelt without being indulgent. It speaks of devotion without demanding context—an achievement Lennon didn’t always manage in this period.

Yet for all its improvements, Mind Games never quite ignites. The craftsmanship is sound, the production polished, but the spark is often missing. Too many tracks settle into mid-tempo amiability and stay there. There’s a sense of Lennon regaining his footing, yes—but also of playing it safe. It is perhaps telling that while the album marked a commercial recovery of sorts, few of its songs remain staples in the Lennon canon. For all its competence, it lacks the urgency or innovation that defined his best work.

Still, Mind Games deserves credit for what it does achieve. It closes the door on a turbulent chapter and reintroduces Lennon as a melodic craftsman. It may not soar, but it doesn’t stumble either. And after the chaos that preceded it, that’s no small victory.

Go back to the main page

Go To Next Review