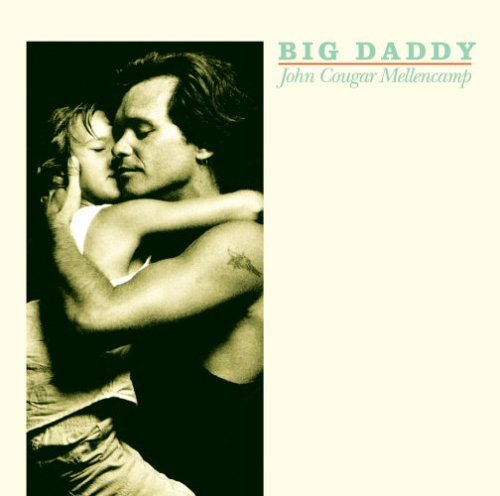

Big Daddy (1989)

1. Big Daddy of Them All

2. To Live

3. Martha Say

4. Theo and Weird Henry

5. Jackie Brown

6. Pop Singer

7. Void in My Heart

8. Mansions in Heaven

9. Sometimes a Great Notion

10.Country Gentleman

11.J.M.'s Question

12.Let it Out (Let it All Hang Out)

With Big Daddy, released in 1989, John Mellencamp closes out the decade not with a bang, but with a quiet, introspective record that trades arena-ready anthems for intimate reflections and rural minimalism. Still drawing from the rustic Americana palette he began exploring with The Lonesome Jubilee, this time Mellencamp strips it down even further. There are fewer hooks, fewer choruses built for radio, and very little traditional “rock” to be found. But what’s gained in return is a sharper sense of character, place, and purpose.

This is arguably Mellencamp’s most personal work to date. The arrangements are sparse, the instrumentation acoustic and lived-in. Gone are the radio-ready flourishes of American Fool and Uh-Huh, replaced by fiddles, harmonicas, and quietly brushed drums. There’s nothing flashy here, and that’s entirely the point. These songs aren’t trying to shout; they’re trying to speak.

Jackie Brown, the album’s emotional anchor, is a masterclass in understated songwriting. Over a simple, mournful progression, Mellencamp paints a portrait of poverty and hopelessness with compassion and clarity. It’s not just one of the strongest moments on the record—it’s one of the finest songs of his career. The subtle power of the track speaks volumes about the evolution of an artist who once made his name with swagger and snarl but now finds resonance in restraint. Elsewhere, Mellencamp continues to dig into social commentary, though not always with the same finesse. Martha Say gives voice to female independence with a raw edge and a catchy refrain, while Mansions in Heaven explores faith and the working-class longing for something beyond. Both show Mellencamp’s knack for empathy, even as his characters wrestle with disillusionment.

Unfortunately, not every moment lands. Country Gentleman, a bitter and ill-conceived swipe at Ronald Reagan-era politics, plays more like a tantrum than a protest. Mellencamp has never been shy about expressing his frustrations, but here the target feels too broad and the delivery too clumsy to leave much of a mark. It’s one of the rare instances where his bluntness becomes a liability rather than an asset.

Still, these missteps are few, and Big Daddy remains a deeply felt and musically assured record. By this point, Mellencamp had passed his commercial peak, but he seemed increasingly comfortable with that reality. He wasn’t chasing hits—he was chasing something truer. And while the album may not have produced any iconic singles, it’s the kind of work that quietly earns its place in the canon.

This is Mellencamp as storyteller, as documentarian, and as craftsman. It may lack the immediate thrill of his earlier records, but Big Daddy rewards the patient listener with some of his richest, most nuanced songwriting.

Go back to the main page

Go To Next Review