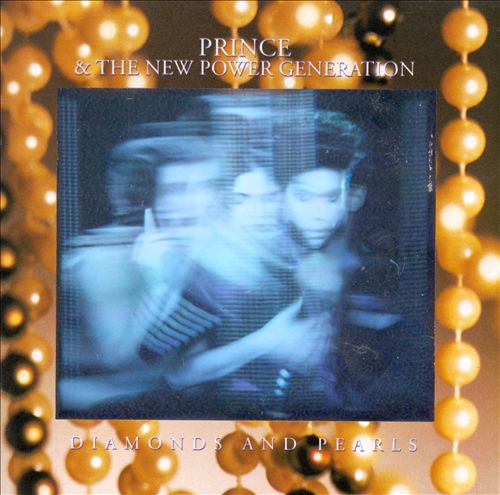

Diamonds and Pearls (1991)

1. Thunder

2. Daddy Pop

3. Diamonds and Pearls

4. Cream

5. Strollin'

6. Willing and Able

7. Gett Off

8. Walk Don't Walk

9. Jughead

10. Money Don't Matter 2 Night

11. Push

12. Insatiable

13. Live 4 Love

At some point while you’re making your way through Diamonds and Pearls, you realize something subtle but unmistakable has happened: Prince has grown up. Not in a “he’s gone soft” sort of way, and not in a “he’s lost it” either. It’s just that the wild, randy, genre-bending lightning bolt who once electrified the early '80s has become, well, a bit more refined. The edges are still there, but they’ve been filed down a touch. The grooves are still funky, but they no longer snarl. You can still dance, but you probably won’t break a sweat. In short, Prince had entered the 1990s with a glossy, adult-contemporary sheen. And it somehow works.

That’s not to say this album lacks range or personality—it has both in healthy supply. In fact, one of the more striking things about Diamonds and Pearls is just how varied it is. From light funk and jazz to silky ballads and modest club tracks, Prince covers a lot of ground. The key difference is that he sounds a little more measured now. It’s not the lyrics—those are still clever and occasionally cheeky—but the music itself that feels more aware of its audience. Prince seemed to understand that many of the fans who grew up with 1999 and Purple Rain were now in their thirties, with jobs, families, and maybe even mortgages. And instead of leaving them behind, he grew with them.

Even the album’s most overt attempts at funk—Jughead and Push—feel somewhat sanitized when compared to his nastier, sweatier work from a decade earlier. It’s telling that the album’s biggest hits are also its smoothest. Cream is practically effortless in its slinky, tongue-in-cheek cool. Money Don’t Matter 2 Nite is laid-back but sharp, a sly social commentary disguised as easy listening. And the title track? One of his most beautiful ballads—soft, melodic, and just sentimental enough. It’s also the kind of song that a kid could play in the living room without getting a lecture, and their parents might even stick around to listen.

The New Power Generation gets full billing this time around, and it shows. The arrangements are dense, layered, and often quite busy. At times, the album almost feels like a spiritual sequel to Graffiti Bridge—not in terms of content, but in the way that there’s always something happening. Fortunately, Prince was still Prince, and he navigates the controlled chaos with ease. Songs like Daddy Pop and the breezy Strollin’ show off a more playful, genre-hopping side that doesn’t always land but is rarely dull. The fact that Prince can move from light jazz to soulful pop without blinking is just another reminder of how effortlessly eclectic he was at his peak.

Still, the album runs a little long—cutting ten minutes might have helped tighten things up—but overall, Diamonds and Pearls is a confident, polished, and surprisingly accessible record. That sense of daring experimentation Prince was once known for has been tempered, but not abandoned. You do start to feel, though, that the Prince of the early ‘80s—the scrappy kid holed up in his personal studio with a head full of ideas and zero rules—is probably gone for good.

This would also be the last album released before Prince’s very public spat with the music industry, which saw him shed his name in favor of an unpronounceable symbol and begin his stretch as The Artist Formerly Known as Prince. In hindsight, the theatrics did more to distract than to elevate the music, and the posturing often got in the way of what really mattered: the songs. But here, at least, he strikes a strong balance. Diamonds and Pearls may not redefine him, but it proves he could still surprise us—even in a suit and tie.

Go back to the main page

Go to the Next Review