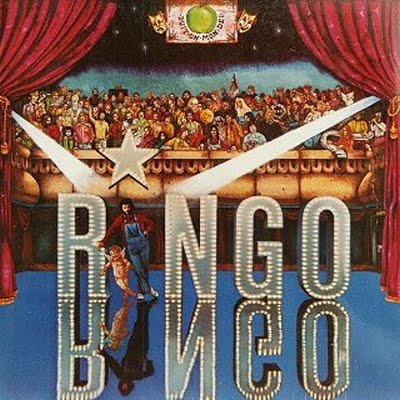

Ringo (1973)

1. I'm the Greatest 2. Have You Seen My Baby? 3. Photograph 4. Sunshine Life for Me (Sail Away Raymond) 5. You're Sixteen (You're Beautfiul and You're Mine) 6. Oh, My My 7. Step Lightly 8. Six O'Clock 9. Devil Woman 10.You and Me (Babe) 11.It Don't Come Easy 11.Early 1970 12.Down and Out

If Ringo Starr’s first two solo ventures—tributes to big band standards and country-western heartache—raised eyebrows for their thematic eccentricity, his self-titled third album arrived as a welcome surprise. Released in 1973, Ringo not only signaled a return to the kind of music fans had quietly hoped for, but delivered with a level of polish, cohesion, and sheer likability that few had anticipated. It is, without question, the finest solo album of his career—and one of the only ones that can comfortably sit alongside the better post-Beatles output of his former bandmates.

The album’s great strength lies in its identity. Unlike his previous records, which leaned heavily on genre pastiche, Ringo offers a set of songs that sound like what most listeners wanted all along: Ringo Starr doing “Ringo songs”—easygoing, melodic, occasionally sentimental, and always carried by that familiar, friendly voice. The irony, of course, is that by stepping away from musical novelty, Starr finally found a formula that fit.

The Beatles connection looms large. All three former bandmates make appearances in various capacities, though never all on the same track. John Lennon contributes the opener I’m the Greatest, a self-aware, tongue-in-cheek number that plays more as a winking nod to Beatles nostalgia than a serious musical statement. It’s the one track that feels more like a reunion stunt than an actual song, and ironically, it's the weakest of the bunch.

More effective is George Harrison’s Sunshine Life for Me (Sail Away Raymond), which wears its Harrisonisms proudly—jangly guitars, lilting rhythms, and an unforced pastoral charm. Paul McCartney’s Six O’Clock is similarly unmistakable: all melody, sentimentality, and soft-focus pop charm. Schmaltzy? Absolutely. Effective? Undeniably. Each contribution, though modest in scope, lends the album a spirit of camaraderie that is impossible to ignore.

Yet it’s not just the guest list that elevates Ringo. Starr himself steps up, contributing co-writes to several of the album’s strongest tracks. Photograph, penned with Harrison, is a genuine standout—not only commercially (it became a major hit), but artistically. It’s wistful, melodic, and emotionally resonant in a way that few expected. Oh My My and Devil Woman show his knack for breezy rockers with just enough grit to keep things interesting. Even You’re Sixteen, a cover of the Sherman brothers’ teenage love song, is pulled off with charm and swagger—helped along, incidentally, by McCartney’s kazoo impersonation.

The album isn’t without its indulgences. The closer, You and Me (Babe), descends into a bit of self-congratulatory stage patter, with Ringo offering a “thank you and goodnight” monologue that would have been better left off the final mix. It’s a minor misstep, but it underscores the sense that this was more than just an album—it was a celebration. And like many celebrations, it perhaps overstays its welcome by a few minutes.

Later reissues added a few non-album tracks, including the essential It Don’t Come Easy, which only enhances the package. But even in its original form, Ringo is a rare feat: a solo album from the Beatles’ least likely hitmaker that not only works, but works remarkably well.

It may not be innovative, and it certainly isn’t profound, but Ringo is everything a pop record should be: warm, accessible, and effortlessly enjoyable. In that sense, it’s the most Ringo album Ringo ever made.