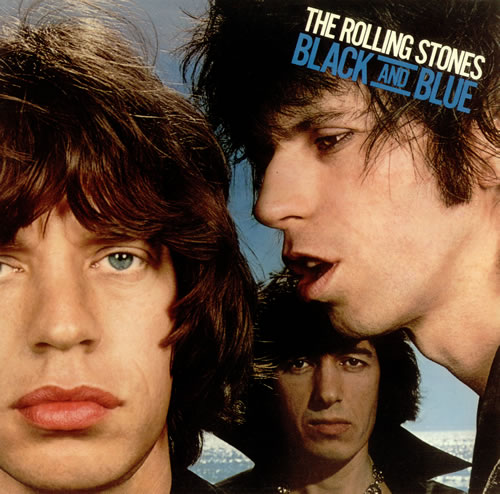

Black and Blue (1976)

1.Hot Stuff

2.Hand of Fate

3.Cherry Oh Baby

4.Memory Motel

5.Hey Negrita

6.Melody

7.Fool to Cry

8.Crazy Mama

It has become fashionable in certain circles to consign Black and Blue to the ever-expanding drawer labeled “mid-period mediocrity”—that hazy region of the Rolling Stones' catalog stretching loosely through the early-to-mid 1970s. And yet, for those willing to listen with fresh ears, this particular record reveals itself as not only underrated, but possibly the band’s most misunderstood effort of the decade.

Following the departure of Mick Taylor, the band entered a state of flux. With no official replacement in place during their 1975 tour, Ron Wood—borrowed from The Faces—was enlisted as a temporary stand-in. His chemistry with the band was instantly apparent, yet the group used the recording sessions for Black and Blue as a sort of public audition, testing out a series of guitarists in real time. It is perhaps this element of experiment, this sense of the band being in between identities, that led many to dismiss the album at the time.

And yet what we find is a surprisingly cohesive and musically compelling record. The album leans heavily on instrumental interplay—riffs, grooves, jams—and this emphasis, while off-putting to some, is precisely what gives the album its distinct flavour. The Stones, after all, have always been a guitarist’s band, and here the guitars take full command. From the tight, muscular swagger of Hand of Fate to the closing crunch of Crazy Mama, the fretwork throughout is masterful, weaving funk, blues, and soul into the band’s well-established rock tapestry. Even the relatively repetitive Melody, with its slow burn jazz-funk lope, offers enough nuance and texture to justify its inclusion.

Not everything lands. The album opens rather shakily with Hot Stuff, a disco-inflected number that, while rhythmically tight, suffers from over-repetition. The central riff is effective, but it is asked to carry too much weight. One gets the sense that the Stones are still testing their versatility—and while they can do disco, here they don’t quite own it.

Where Black and Blue truly surprises is in its most introspective moments. Memory Motel and Fool to Cry, both minor hits in their own right, are astonishingly well-crafted and emotionally resonant. Each opens with a restrained electric piano figure, gently ushering in some of the most contemplative lyrics the band had penned in years. There is a softness to these tracks, a welcome contrast to the album’s more rhythmic excursions, and their placement gives the record a sense of narrative structure rather than mere sequencing.

In many ways, this is the most accessible album the band had released since Exile on Main St.—not in the sense of radio-readiness, but in its easy, open confidence. Black and Blue does not try to be a definitive statement. Instead, it is exploratory, transitional, and ultimately rewarding—precisely the sort of album that reveals its charm over repeated plays. It may have sounded like an audition at the time. Today, it sounds like a quietly assured success.

Go back to the main page

Go To Next Review