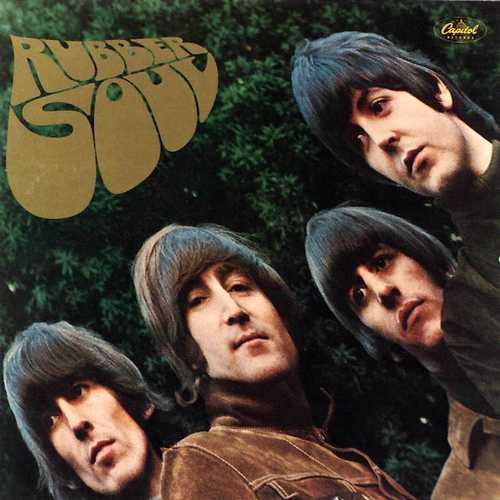

Rubber Soul (1965)

1.Drive My Car

2.Norwegian Wood

3.You Won't See Me

4.Nowhere Man

5.Think For Yourself

6.The Word

7.Michelle

8.What Goes On

9.Girl

10.I'm Looking Through You

11.In My Life

12.Wait

13.If I Needed Someone

14.Run For Your Life

With the hysteria of Beatlemania beginning to subside by the close of 1965, the Beatles found themselves at a rare creative crossroads—less beholden to the demands of screaming audiences, and newly emboldened by the cultural space their success had afforded them. The result was Rubber Soul, a work that many critics regard as the band’s first truly mature album. It was also, quite clearly, the opening shot in a creative revolution that would culminate in the seismic releases that followed.

There is a pronounced shift in tone here—more introspective, more nuanced, and markedly more experimental in both style and content. Influenced by their growing infatuation with Bob Dylan and their increasingly casual relationship with cannabis (reportedly introduced to them by Dylan himself), Rubber Soul is often cited as the moment the Beatles stopped being merely pop stars and started behaving like artists. That distinction, while a touch romanticized, is not altogether inaccurate.

The album opens with Drive My Car, a slinky, piano-propelled rocker with suggestive lyrics and tight harmonies. Its sardonic humor sets the tone for what’s to come. Lennon's Norwegian Wood, one of the most discussed tracks on the album, introduces the sitar to the Beatles’ sonic vocabulary and subtly masks its tale of infidelity beneath exotic instrumentation and dry wit. It is both a musical and thematic departure, and it signals a band beginning to write about adult situations in adult terms.

The highlights are many. Nowhere Man offers one of the first overtly philosophical lyrics in the Beatles’ catalogue, while In My Life—perhaps Lennon’s most emotionally resonant early composition—has assumed near-epitaphic status. The latter is anchored by a Baroque-style keyboard solo from George Martin, elevating what might have been a modest ballad into a work of poignant grandeur.

McCartney’s Michelle, despite its cloying reputation in some circles, is musically intricate and lyrically charming. Its fingerstyle guitar, melodic structure, and pseudo-French affectations remain divisive but undeniably memorable. Likewise, Harrison’s If I Needed Someone—his finest contribution to date—displays a growing confidence in both songwriting and arrangement. Its harmonic structure and jangling guitar are indebted to The Byrds but reshaped through Harrison’s increasingly sophisticated ear.

Of course, not everything is uniformly excellent. You Won’t See Me and Wait, while melodically sound, suffer from a certain sameness of rhythm and pacing. One could be forgiven for mistaking one for the other. Ringo’s What Goes On is pleasant enough but treads familiar country-and-western territory without innovation. Still, even the lesser tracks are executed with the polish and unity that had by now become second nature to the band.

What makes Rubber Soul so significant—aside from its individual highlights—is its coherence. It sounds like an album, not a collection of singles and fillers. The sequencing, the acoustic textures, the willingness to explore new lyrical ground—all of it contributes to an impression of artistic intent. The Beatles were no longer simply producing music for public consumption. They were beginning to make statements.

It is no exaggeration to say that Rubber Soul changed the expectations of what a pop album could be. Without it, the entire notion of the album as a cohesive artistic medium might have taken longer to take root. For the Beatles, it marked the end of innocence and the beginning of ambition. That so many of these songs still resonate today is a testament not just to their craftsmanship, but to their foresight.