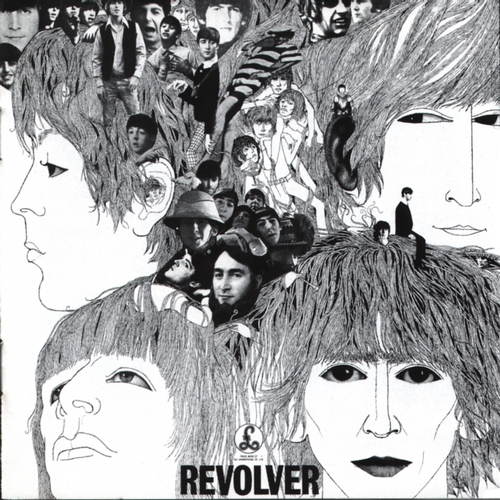

Revolver (1966)

1.Taxman

2.Eleanor Rigby

3.I'm Only Sleeping

4.Love You To

5.Here, There and Everywhere

6.Yellow Submarine

7.She Said She Said

8.Good Day Sunshine

9.And Your Bird Can Sing

10.For No One

11.Doctor Robert

12.I Want To Tell You

13.Got To Get You Into My Life

14.Tomorrow Never Knows

Following the creative leap of Rubber Soul, Revolver arrived in 1966 not as a sequel but as a statement—clear, bold, and transformative. If Rubber Soul was the Beatles' first mature album, Revolver was their first truly modern one. The band had now outgrown the expectations of the pop single, the album-as-afterthought format, and the idea of the Beatles as merely four charming mop-tops. What emerged was a work of startling variety, technical innovation, and artistic daring.

The opening track, Taxman, is a surprisingly aggressive complaint from George Harrison about Britain’s taxation policies. Its sinewy bass line, slicing guitar riff, and sardonic lyrics set the tone for what would be the most sonically adventurous Beatles record to date. That the first voice we hear is Harrison’s—rather than Lennon or McCartney—also signals a quiet but significant shift in group dynamics. Harrison, once the quiet apprentice, was emerging as a songwriter of increasing consequence.

What follows is no less extraordinary. Eleanor Rigby, McCartney’s chamber-pop elegy for loneliness and societal detachment, dispenses with the band entirely—its austere string octet accompaniment and stark narrative a bold departure from conventional pop. Lennon, for his part, continues his descent into introspection and surrealism with I’m Only Sleeping, She Said She Said, and the remarkable album closer, Tomorrow Never Knows. The latter, inspired by Timothy Leary’s reworking of the Tibetan Book of the Dead, is not so much a song as a controlled psychedelic detonation. Tape loops, reverse guitars, and a vocal treated to sound like it’s emanating from another plane altogether—this was 1966, but it sounded like the future.

The middle of the album is no less rich. McCartney’s Here, There and Everywhere is a soft, romantic ballad in the tradition of Yesterday, but with a harmonic sophistication that places it among his most finely wrought compositions. For No One, another McCartney gem, is devastating in its emotional economy—understated, concise, and laced with a melancholic French horn solo that elevates its resigned heartbreak into art song territory.

Ringo Starr contributes Yellow Submarine, a whimsical sea shanty that, while often dismissed as a children’s novelty, displays remarkable production playfulness. That it would later serve as the basis for an animated Beatles feature film is testament to its odd staying power. Harrison’s other contributions include Love You To—a sitar-driven exploration of Indian classical music that predates most of his contemporaries’ flirtations with the East—and I Want to Tell You, a piano-heavy track of rhythmic complexity and lyrical ambiguity.

One of the most astonishing aspects of Revolver is its cohesion. Despite the album’s diversity—psychedelia, classical, soul, baroque pop, Indian raga, children’s singalong—it never feels disjointed. Much of this can be credited to producer George Martin, whose growing influence over the band’s studio process would soon be near-total. The decision to prioritize the studio over the stage—cemented during the Revolver sessions—liberated the Beatles from performance practicality and opened the door to limitless experimentation.

If Revolver does have a weakness, it lies only in the perception of its greatness being occasionally overshadowed by what came next. Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band may have stolen the headlines, but Revolver was the true revolution. It was here, not in 1967, that the Beatles firmly placed themselves at the vanguard of contemporary music.

In the final analysis, Revolver is one of the most vital and enduring albums in rock history—not merely because of what it contains, but because of what it made possible.