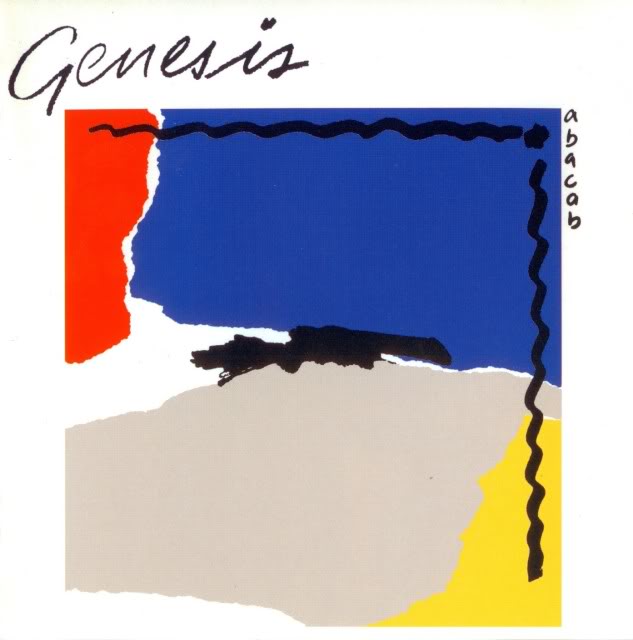

Abacab (1981)

1.Abacab

2.No Reply at All

3.Me and Sarah Jane

4.Keep it Dark

5.Dodo/Lurker

6.Who Dunnit?

7.Man on the Corner

8.Like it or Not

9.Another Record

By the turn of the decade, it was becoming increasingly clear that the Genesis of old—the mystical, multi-part suites and lyrical allegories—was fast receding in the rear-view mirror. Abacab, then, is nothing short of a calculated reinvention. With admirable foresight, the band appeared to recognize that clinging to the vestiges of their progressive past would be artistically stagnant, if not commercially fatal. The 1980s had dawned, and with it came a new sonic vocabulary. Rather than resist, Genesis embraced it—albeit with mixed results.

To aid in this metamorphosis, the band enlisted engineer Hugh Padgham—best known at that point for his crisp, punchy drum treatments and his work with the likes of Peter Gabriel and XTC. His arrival here cannot be overstated. While not the named producer in a formal sense, his imprint is palpable throughout: the gated reverb drums, the sculpted synths, the overall air of modernity. It was Padgham, more than any band member, who ensured that Abacab sounded like 1981 without succumbing to the decade’s more disposable tropes. There is sheen, yes—but never the sort that glitters gaudily or fades with time.

The opening title track, Abacab, serves as a bold, if uneven, manifesto. Built on a simple motif, it flirts with minimalism before spiraling into an extended instrumental that, though brave in intent, becomes oddly inert—seven minutes spent circling an idea that might have said more in half the time. Curiously, the radio edit, now found on some compilations, achieves exactly that with superior effect. Still, as a statement of intent, it succeeds: Genesis were done with fairy tales and twelve-string arpeggios.

No Reply At All, meanwhile, sees the band dive headfirst into R&B waters, horns and all. The involvement of Earth, Wind & Fire’s brass section might have startled long-time fans, but in the wake of Collins’ solo success earlier that year (Face Value), it made a sort of contextual sense. It’s taut, infectious, and—despite being sonically alien to Genesis’ previous output—utterly confident in its delivery.

But then, we come to Whodunnit. A track that, even within the band’s adventurous canon, stands as something of a sore thumb. A synth-heavy, deliberately obtuse excursion into musical whimsy, it elicited outright derision when performed live—boos, no less, from audiences unprepared for such frivolity. Yet there is a strange bravery in its inclusion, as though Genesis were daring their audience to follow them into absurdity. Not their finest hour, perhaps, but not entirely without merit in the broader context of artistic risk.

Elsewhere, the album steadies itself. Each member was granted one solo-penned composition, and while the distinctions aren’t overly pronounced, they lend the record a sense of collaborative parity. The remaining tracks are group efforts, and it shows—there’s a unified aesthetic, a cohesive drive behind the material, even when the individual songs vary in impact. The album's blend of electronic textures and rhythmic immediacy marked the beginning of a new Genesis—less esoteric, more streamlined, and, crucially, more in tune with the decade to come.

One final note of curiosity: this was the first Genesis album to feature a photo of the band on the sleeve—a symbolic gesture, perhaps, of a band willing to step out of the shadows and into a more visible, public-facing role. If Abacab didn’t please everyone, it nonetheless cleared the path for the mass success that would soon follow. The chrysalis had cracked. The transformation was underway.

Go back to the main page

Go To Next Review