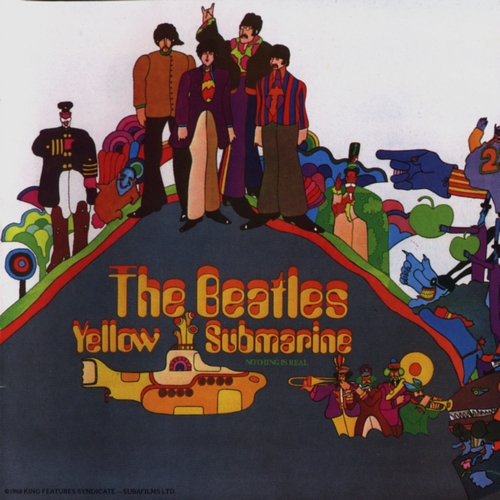

Yellow Submarine (1968)

1.Yellow Submarine

2.Only A Northern Song

3.All Together Now

4.Hey Bulldog

5.It's All Too Much

6.All You Need Is Love

7.Pepperland

8.Sea of Time

9.Sea of Holes

10.Sea of Monsters

11.March of the Meanies

12.Pepperland Waste

13.Yellow Submarine in Pepperland

Of all the Beatles' core releases, Yellow Submarine remains the most anomalous—part soundtrack, part compilation, part contractual fulfillment. While its name is more often associated with the 1968 animated feature film (a whimsical, often psychedelic odyssey loosely tethered to the Beatles’ universe), the album itself occupies a curious space in their discography: not quite a proper studio effort, and definitely nowhere near a greatest hits package. And yet, despite its patchwork origins, the record still offers musical rewards that deserve a more generous assessment than it often receives.

The album opens with the title track, originally lifted from Revolver, and instantly familiar for its childlike singalong chorus and Ringo Starr’s disarmingly affable delivery. Though it had already been a hit two years prior, its inclusion here serves more as thematic branding than artistic necessity. All You Need Is Love, similarly recycled, closes the first side—an idealistic anthem that had already achieved global recognition after its live broadcast during the 1967 Our World satellite program.

Between these two known quantities lie four new Beatles recordings—each offering a distinct flavor. Only a Northern Song, a previously unreleased George Harrison track from the Sgt. Pepper sessions, is notable for its sardonic tone and deliberate use of studio dissonance. It is less a song than a meta-commentary on song publishing rights, making it more significant than enjoyable. All Together Now, a McCartney-led ditty, aims squarely at the film’s youthful audience—jaunty, simple, and bordering on the twee (with one eyebrow-raising lyric that hardly suits the nursery tone). More impressive are Hey Bulldog and It’s All Too Much, the former a driving Lennon rocker built on a gritty piano riff, enlivened by some of the most playful studio banter the Beatles ever captured on tape. Long overlooked, it is now rightly recognized as one of the band’s most muscular late-period tracks. Harrison’s It’s All Too Much, meanwhile, is perhaps the hidden gem of the album: sprawling, psychedelic, and underpinned by layers of feedback, horns, and exuberant excess. It may overstay its welcome, but its ambition is undeniable.

Side two consists entirely of orchestral score composed and arranged by George Martin. Though this music formed the backdrop of the film’s fantastical landscape, its inclusion on the album has long been debated. As a standalone listening experience, it is atmospheric but nonessential. Yet Martin’s work here is not without merit. Pieces such as Pepperland and Sea of Time possess charm and aural wit, even if they rarely invite repeat listening. That Martin would later score a James Bond film (Live and Let Die) is perhaps foreshadowed in these whimsical instrumental sketches.

In 1999, the album was reimagined as Yellow Submarine Songtrack, replacing the orchestral content with all Beatles songs featured in the film. While a more cohesive listening experience, it came at the expense of the original’s historical and conceptual integrity. The original Yellow Submarine, for all its unevenness, is a more accurate document of the Beatles’ late-’60s multiverse: fractured, playful, and never entirely serious about its own mythology.

If Yellow Submarine is not a great Beatles album, it remains a necessary one. It captures, in miniature, both the band’s artistic overreach and their refusal to be confined by standard formats. It may not be essential listening for the casual fan, but for the completist—and for those willing to dig beneath its novelty exterior—it holds more substance than its reputation suggests.

Go back to the main page

Go To Next Review